Dispatches – Pittsburgh’s my kind of town. The kind of town into which you feel you ought to have come by train.

Something about the place invites back the train.

All the brick and stone and steel, the corridors and edges. The vast central cemeteries with open gates, forking paths for the living as much as the dead. Geese flying loud and low, over layers of working neighbourhoods, over steady persistence and sprouts of gentrification. Above all, topography. Hills, valleys, ravines, rivers and streams, but then also streets and strips and squares. Buildings upon buildings, churches upon churches. And all the bridges.

Pittsburgh’s beauty is loose on the land and over the waters. It’s topographical.

An unlikely configuration of natural and physical features, of human positioning, risen and faded, risen and faded again.

I came to Pittsburgh —on the last day of January, 2025— to see a play about an eighteenth-century Quaker dwarf named Benjamin Lay. It turned out to be the best and most timely of calls.

Born into a Quaker family in England, Benjamin Lay (1682-1759) took ship to what was then the colonial realm of Barbados, where he ran a small shop with his beloved. It was there that he came face-to-face not only with slavery’s savage brutality but also with its normalisation among all kinds of people, very much including Quaker leaders and other members of the white élite who —here, there, and everywhere— fancied themselves charitable, considerate, civilized, upstanding, forward-looking, even revolutionary.

After he left Barbados and settled in Pennsylvania, he sought out the meeting houses of the Quakers again, so influentially present in these lands. He was hoping for community and something better. But Lay proved too intellectually restless, too morally and socially radical for his fellows here as well. He was an abolitionist and an advocate of animal rights. He wrote and disseminated inflammatory texts, he spoke deliciously.

It was doubtless thought by the disapproving Quaker leadership that ultimately cast him out that Benjamin Lay would finally be silenced, that he’d crawl off into some cave, disappearing into grumpy obscurity. Well, he would find a cave, but thanks to the historical curiosity and cross-temporal solidarity of a few, Benjamin Lay is no longer so obscure.

I scribbled many words and phrases across the margins and in the blessed blank pages at the back of the script written by Naomi Wallace and Marcus Rediker.

A dramatic vision inspired by Benjamin Lay, and much buttressed by Rediker’s groundbreaking study of this neglected figure, The Fearless Benjamin Lay.1

I’ll share just a few of Lay’s words and phrases, and just a bit of the story that unfolded so powerfully on the stage. For I don’t want to give it away. What I want is for you to drop everything and find your way to a performance of this one-man play. Having world-premiered in London’s Finborough Theatre in 2023, I took in the USAmerican premiere on 31 January 2025 in Pittsburgh. Directed by Ron Daniels, this Quantum Theatre production continues at the Braddock Carnegie Library in Pittsburgh until 23 February. It moves to New York City’s Sheen Center (14 March to 6 April 2025), and then, appropriately enough, on to the Quintessence Theatre in Philadelphia (1-18 May 2025).

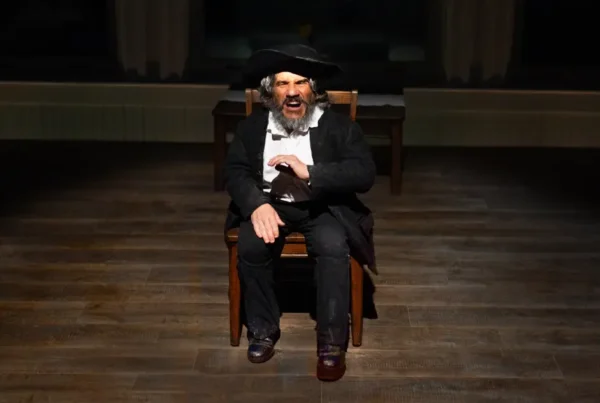

In “The Return of Benjamin Lay,” the activist comes back to life to plead his case upon a stage before us. Even as we, his modern audience, are transformed by the magic of theatre into the very eighteenth-century Quaker community that has expelled him, we find much that chases and chafes our sensibilities, that resonates with our twenty-first-century here and now.

Experience with the Royal Shakespeare Company shines through Daniels’ direction. Even so I would have liked to be in the room as the extent of the actor Mark Povinelli’s talents became clear.

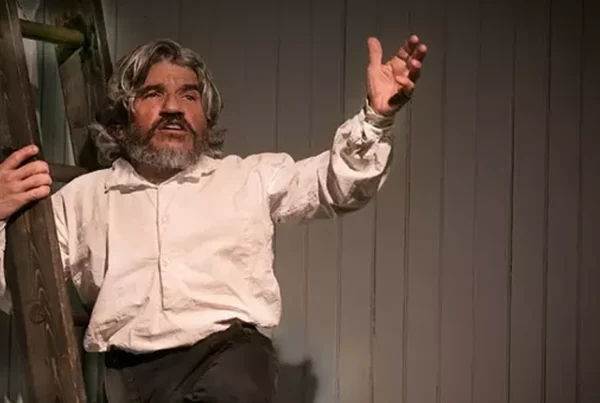

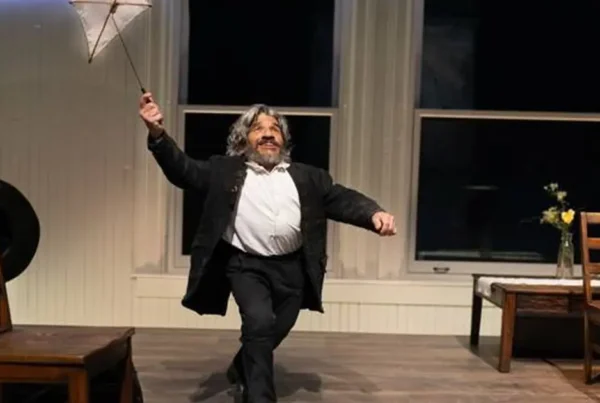

What stood out to me in particular was how the playwrights and director and this extraordinary actor realise the centrality and art of embodied language. It’s eighteenth-century speech, it’s salty sailors’ talk, it’s common conversation, it’s Quaker pronouncements, it’s the rebel’s pamphlet. Above all, it’s an expression of what Lay felt in Barbados, “a dark shadow of horror remains in me,” and his dedication to speaking his conscience, to risk prison and exile. Povinelli’s Benjamin Lay embarks on a meander of critical word play, rushing about the stage in an extraordinary performance of just over seventy minutes.

“Sisters and brothers, do you know what sugar is?,” Lay stirs further. “In the tea it makes a little heaven for the tongue,” but “sugar is made of blood.”

And “how is your bleat?,” the four-foot-tall Lay asks the audience, before likening himself to a lamb. Not a lamb who’s innocent and loved. But one who’s laughed at, his body mocked, his writings spurned and banned, the “mouthy midget.” “You are looking at me now,” he suddenly challenges, “but do you see?”

A vehicle for this series of voices and bodily gestures, Povenilli’s Lay replays his own memories but also the voices and bodies of a string of other characters and remembered dialogues. He’s back in Bridgetown with his friend, an enslaved Igbo captive, the “handsome and smart” Bussa, who “said my name . . . Ben-jahh-meeen . . . as though it had never been said before.”

He’s recalling the Quaker director casting him out of the community. He’s in a bonnet. He’s up a ladder.

He recalls the cave in which he dwelt, alone except for his “milk and honey,” which is to say his “two hundred books of all kinds and sizes.” He prefers that cavern to what his audience the Quakers ultimately afforded: “the quiet is good for the soul,” he tells them/us, “and it reminded me of the tranquility I’d lost with you.” He prefers that cavern to what he has seen of the powerful, the would-be emperors and their self-serving henchmen. “Vermin come in packs,” remarks Benjamin Lay.

He’s on a table, suddenly King George II, an arm and banner on high, bellowing about his wealth of colonies and how his cape “swarms with a hundred animals that still blink when I caress them, sewn with a thousand silk threads —” , before he becomes Benjamin again to add and remind “made by the tiniest, fine-iest hands in India.” “Oh India!” bellows Benjamin, arm aloft, once again the king.

There are moments in the script in which Benjamin Lay interacts directly with members of the audience.

If only I had sat in a more central spot, I might’ve been the audience-member who got to help Benjamin Lay into the bit of armour he donned, dressing for moral battle in one of the scenes. When he singles another person out, with “what are you reading right now?!” it could have been me answering “Olga Tocarczuk!” And I’m just a little disappointed when the Pittsburgh production passes (doubtless for good reasons of safety) on the opportunity afforded by the script’s ending, to have members of the audience join Povenilli on stage.

The story has been told. It’s incomplete and reverberating.

It’s the nature of humankind that nothing of this sort is over.

“Come then. Join me,” responds Benjamin Lay. “We can make the finest work of one another, loving and levelling all things, great and small. Come stand with me. Let’s talk.”