The Pittsburgh Tatler – Hypocrisy is in the air, dear Reader.

No, I’m not talking about the shitshow in Washington, although obviously it hangs thick there; rather, I’m talking about what’s on our local stages, and, in a weird synergy, a common thread of the two solo performances currently running.

I’ve already written about the barebones production of Unreconciled, which aims its ire at the self-serving Catholic Church. Quantum Theatre’s The Return of Benjamin Lay directs its fury at the hypocrisy of early 18th-century American Quaker slaveholders, who not only found ways to reconcile slavery with their theological principle of brotherly love, but also actively shunned and banished abolitionists – like Benjamin Lay – who called them out on the dissonance between their beliefs and their actions.

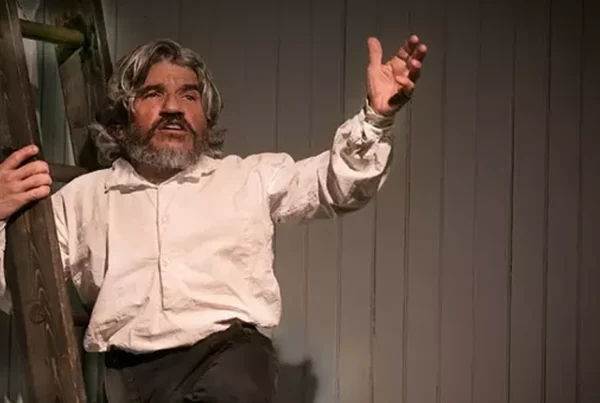

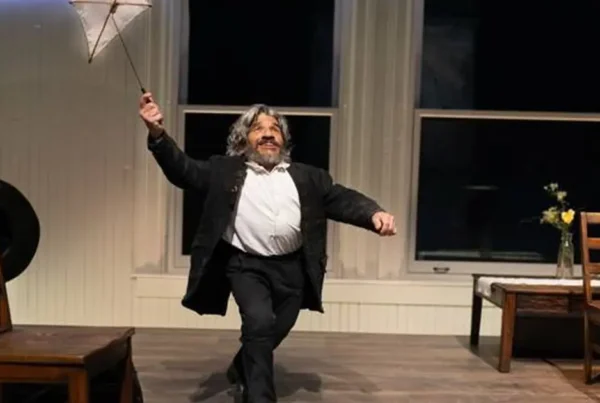

Writers Naomi Wallace and Marcus Rediker frame the performance event as a Quaker meeting in Philadelphia – with the audience serving as the congregation of Friends – to which Benjamin Lay (Mark Povinelli) has returned to petition for his reinstatement to Quaker membership. This objective drives him to recount his personal history and the development of his abolitionist principles: born in England into a Quaker family, he took to sea as a young man and eventually wound up in the British sugar colony of Barbados, where he and his wife Sarah were appalled by the brutal treatment of enslaved people, and in particular by the mercilessness displayed by Quaker slaveholders. His publication in 1736 of an impassioned anti-slavery pamphlet, “All Slave-Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage: Apostates” – which specifically called out Quaker slaveholders as “Pretending to lay Claim to the Pure & Holy Christian Religion” – along with his tendency to disrupt Quaker meetings and make dramatic demonstrations (including kidnapping the child of slaveholders to give them a taste of their own cruelty) prompted multiple Quaker communities to disown him. Yet he remained committed to the Quaker faith, and the play presents his desire to be reinstated as both a need for community and an ardent attempt to convince his fellow Friends of the error of their ways in continuing to live out of harmony with their religious principles.

Povinelli – who, like the historical Lay, stands at around four feet tall – imbues his personation of Lay with the fervor of the passionate true believer. In real life, Benjamin Lay was one of those rare individuals who rigorously lived in accordance with his values: he refused to purchase any goods produced by the exploitation of others, at one point living in a cave, growing his own food, and weaving his own clothes from flax. Povinelli’s performance is most impactful in the moments when his character’s actions “then” cathect with our “now,” as when he asks us – as his fellow Quakers – whether we put sugar in our tea, an action he equates to drinking the blood of enslaved people. It’s not hard to connect the dots between that tainted act of consumption in the 18th century and the contemporary wearing of fast fashion, use of cell phones, purchase of fish, or the consumption of any number of global commodities produced with the labor of violently exploited and/or enslaved people. The subject of this play is a historical one, yet also supremely timely: when (as now) the righteous find it convenient – or enriching – to act in opposition to their stated values, we need figures like Benjamin Lay to model how to be a courageous and effective thorn in their side.