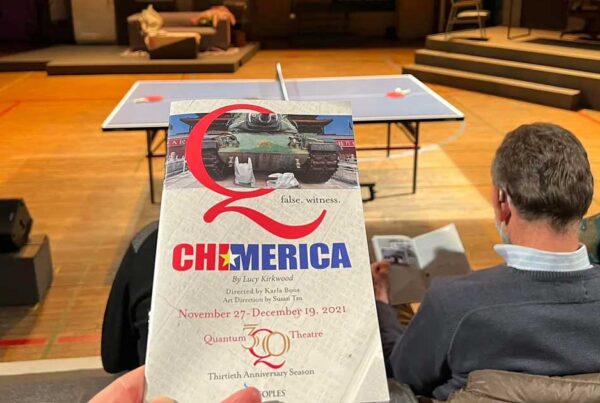

The Pittsburgh Tatler – The spine of the story in Lucy Kirkwood’s award-winning 2013 play Chimerica is relatively simple: an American photographer who captured the iconic image of an unknown man standing in front of a tank in Tiananmen Square in 1989 comes to believe, 23 years later, that “tank man” is alive and living in New York, and the photographer embarks on a hunt to find him so that he can tell his story. But nothing is simple when it comes to China – and particularly US relations with China, particularly as China emerged as an economic juggernaut in the late 20th century – and Kirkwood’s ambitious play seeks to capture, through the multiple tendrils attached to that spine of a story, the complicated and sometimes contradictory forces that have shaped lives and fortunes both in China and the US over the past three decades.

The play’s action is set primarily in the fall of 2012, when Obama was running for re-election, a context that feels important in retrospect because of the demonization of China in the 2016 election cycle – that is, hindsight allows us to see how the benefits reaped by China from economic globalization in the early aughts created the conditions for a populist-nationalist backlash here in the US. But the setting is important for another reason as well, as it sets up a dynamic on both the macro and the micro level of American arrogance and naiveté when it comes to foreign relations. On the macro level we see both politicians largely turning a blind eye to what is happening in China, and corporations blundering their way into an economy they can barely begin to comprehend. As one character, the market analyst Tessa (Alison Weisgall) observes, cultural incompetency was a prime reason that many Western conglomerates initially failed in their attempts to introduce their products and services to the Chinese consumer; the ones that succeeded, like KFC, craftily adapted to Chinese customs and expectations (by, for example, adding congee to the breakfast menu).

On the micro level, we see our protagonist, photographer Joe (Kyle Haden), leave all manner of collateral damage in the wake of his single-minded and obsessive pursuit to find the subject of his most famous shot. Although he speaks Mandarin, was witness to the massacre at Tiananmen Square, and has not only visited China multiple times but also made friends in the country, he is curiously blind to both its socio-cultural expectations and the dangers faced by its citizens: he fails to live up to a promise he makes to his friend Zhang Lin (Hansel Tan) to make contact with his nephew Benny (Tobias C. Wong) who is going to school in New York; he thoughtlessly puts Zhang Lin in danger by texting him a potentially compromising photo; and his actions inadvertently result in the deportation of Chinese refugees living illegally in the US. One explanation for this heedlessness might be that the character of Joe is just a careless and self-absorbed asshole, but I suspect that Kirkwood intends us to understand this carelessness and self-absorption thematically, as a stand-in for the way the US exercises a blindly arrogant foreign policy.

Another thread pulled by the play involves the risks of snuggling up with a partner you don’t fully understand. This is highlighted by a long presentation that Tessa gives to the financial company for which she has prepared a market analysis, in which she warns about the dangers of extending credit and mortgages to 1.3 billion people who are unversed in the workings of a credit and debit economy; it’s also evident when newspaper managing editor Frank (John Shepard) explains that he can no longer support Joe and his writing partner Mel’s (Jason McCune) investigation into the whereabouts of the tank man because the paper is about to be purchased by a conglomerate with financial backing from (you guessed it) China. Yet another of the play’s interests centers on the environmental impact of China’s economic boom: a running theme in the play is the terrible air pollution in Beijing, which is so noxious that residents must wear masks outdoors, yet is officially “disappeared” by governmental air quality reports with fictitiously low numbers.

The play’s emotional core is occupied by the character of Zhang Lin, who, as a young man (played by Tobias C. Wong), participated in the Tiananmen protests with his young wife (played by Ariel Xiu), who became a victim of its violence. In 2012 he is an English teacher who occupies his free time sitting on his couch and numbing his memories of those traumatic days with alcohol. But the untimely death of a neighbor (Mimi Jong) from smog-induced emphysema kindles him into renewed political activism, with predictable consequences: the China of 2012 is no more open to citizen protest and criticism than the China of 1989. Hansel Tan does a terrific job of conveying the conflicting desires that tear at the heart of this character: the anguish and anger that pulls him toward action and the fear that holds him back; the idealism that drives him to speak out and the cynicism that enables him to accept his fate. While Joe’s actions drive the story of the play forward, Zhang Lin is its hero, and Tan shapes the contours of the character’s quiet heroism with precision and clarity.

Under Karla Boos’s direction, the many threads of the play are tied together by an ensemble of actors playing multiple roles in episodic scenes that show how interconnected we are by the forces of globalization. Brian Kim plays the dual roles of Zhang Lin’s brother, who is made vulnerable by Zhang Lin’s political activism, and Wang Pengsi, an undocumented refugee in New York, whose life is upended by Joe’s meddling inquiries. Elena Alexandratos and John Michnya play both a senator and her aide and two high-level internet execs, in both cases representing the compromisable agents whose decisions have direct impact on individuals like Zhang Lin. Mei Lu Barnam and Mimi Jong play multiple characters in both New York and Beijing, including a refugee sex worker and her boss, and the young beneficiary and older victim of China’s economic boom; here, too, the dual casting helps connect the dots between macro socio-economic forces and their micro effects on individuals. Jong also provides beautiful musical accompaniment to many of the scenes both vocally and on traditional instruments.

At times this is a play that feels like it’s got more balls in the air than it can successfully juggle, as it tries to map out how parties with good intentions – like journalists, activists, and politicians – come to betray the people and causes they believe they serve. It’s certainly a play that – despite its grounding in an image that has come to symbolize the power of a single person to stand up to the force of the state – in the end seems pessimistic about the use of peaceful protest and activism to dismantle systems of power and oppression. Indeed, the story told by Chimerica stands rather as a warning about our complacency with those very systems, which are designed, like tanks, to crush whatever stands in their path: we can’t always count on there being principled heroes at the wheel who refuse to do so.