Entertainment Central Pittsburgh – One thing you must say about playwright Jay Ball’s adaptation of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari: Amid the spookiness and the grim foreboding of bad things waiting to happen, he has worked in a good bit of humor. Some of it is pretty darn tricky.

The original Caligari, a silent horror film, premiered in Germany in 1920. Ball’s version resets the action to communist East Germany in 1970, when that half of a then-divided nation was part of the Soviet bloc. There’s a scene in which three friends—two young men and a young woman—go out for fun, visiting a street fair. But the street fair is rather different from the one in the movie. At center stage is a kissing booth. An attractive lady stands behind a sign that reads WORKERS OF THE WORLD, KISS ME.

The three friends eye the booth, pondering whether to give it a try. Says one of the men, “Are we not workers?” Says his buddy, “No, we’re young professionals.”

And there you have a multi-layered punch line. It refers not only to the Marxist distinction between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, but also to the tensions in present-day America. We live in a country where members of the so-called working class and the so-called thinking class perceive themselves, others, and the state of the union in radically incompatible ways. Which leads a person to wonder: Has it really come down to this? That in the United States, a deeply capitalist, anti-communist nation, it all comes back to class struggle anyway? Was Marx right after all? Or was he just Left, or what???

The Layers of a Dizzy Labyrinth

Quantum Theatre is presenting The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari through November 24. The play has many intriguing features, but if you’re going, be forewarned that it is more than a live-theater remake of a classic film. It draws you into a labyrinth of mixed meanings and cognitive dissonance. The script spins a multi-layered web, and the stagecraft—which combines live acting with stunning projections of old film clips and newly created images—deepens the dizziness.

Indeed, so much goes on in the play that perhaps it will help to be armed with a backstory. The backstory itself gets complicated, so let us start with the 1920 film.

Backstory: the Film

Germans in 1920 lived in a society, and a world, of dramatic changes. Germany’s headstrong World War I campaign had left a sizable number of the population killed or mangled. Defeat had driven the autocratic Kaiser Wilhelm II to abdicate, thrusting Germany into the chaotic early stages of the Weimar Republic. And yet hope and energy welled up anew. In Germany as elsewhere, people were getting caught up in the giddy excesses of the Jazz Age and the thrill of new mass-market technologies—from radio to, well, movies.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari arrived on screens as a cautionary tale. The scriptwriters were two young German pacifists who hoped their fellow citizens would nevermore be marshalled into another grotesque war. They scripted a surreal horror tale about a mad doctor who casts a spell on a somnambulist—a sleepwalker—inducing him to commit ghastly murders. The social message couldn’t have been clearer: We must be wary of sleepwalking under the spell of mad dictators.

As things turned out, the message didn’t stick. Within 13 years of the film’s release, the Weimar Republic devolved into Nazi Germany. After millions more had died in the Second World War, a German cultural critic even wrote a book titled From Caligari to Hitler.

But does the film’s theme still resonate? In the 2024 stage version produced by Jay Ball and the Quantum team, it resonates amid overlapping echoes of history and time.

Backstory: the Play

When the lights go up, a text projection tells us we’re in Berlin in 1970. And the opening scene, a framing device, tells us we’re about to see a play within a play. A graying woman in a wheelchair, wearing an oxygen mask tubed to a reserve tank, is wheeled to a microphone at a podium. The woman is theater artist Helene Weigel, widow of the late Bertolt Brecht, and now artistic director of the Berliner Ensemble acting company.

Weigel (played with convincing drama by Catherine Gowl) is a passionate socialist. Ignoring doctor’s orders, she rises from the wheelchair and addresses the audience as “Dear comrades.” She says we’re here for the purpose of “building socialism,” which has enabled East Germany to rebound from the rubble and devastation of World War II, creating a workers’ paradise “where every day a new apartment block rises.”

But the younger generation, says Weigel, cannot remember the lessons of history. They’re oblivious to the terrors wrought in the past by a mad Kaiser, and then a fascist dictator. Therefore, Weigel booms, “Our company is making an attempt to remember what should be remembered”—namely, that “in our reborn city, the horror is still out there.” Thus begins—so we are told—the Berliner Ensemble’s 1970 adaptation of 1920’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

Got that? Maybe you also noticed that in Weigel’s speech, irony abounds. East Germany in the 1970s was hardly a workers’ dreamland. It was a country that had to build a wall across Berlin to stem the exodus of citizens trying to escape the social repression and economic inefficiency of the Soviet-backed regime. The “horror” that Weigel warned of, perhaps some mixture of neo-Naziism and Western capitalism, was in fact a horror within a horror.

If you got that, you should be ready for the rest of Caligari.

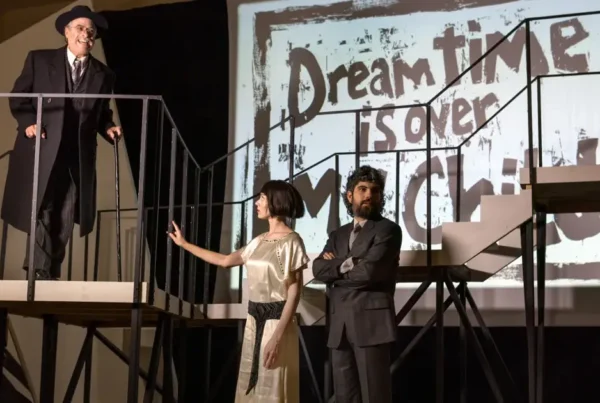

Franz (Nick Lehane, L) seems to have a premonition the future won’t be rosy when he and Hannah meet Dr. Caiigari (Daniel Krell).

Into the Whirlwind

Plot-wise, the play more or less follows the movie. Our friends at the street fair are lured to a sideshow run by the mysterious Dr. Caligari (Daniel Krell). The doctor introduces his creepy somnambulist, Cesare (acted chillingly by Jerreme Rodriguez). Awakened from sleep, Cesare displays an all-knowing vision of the future. When young Franz (Nick Lehane) asks how long he, Franz, will live, Cesare answers: not until dawn. In the next scene, cold-eyed Cesare fulfills the prophecy by sneaking into Franz’s quarters and knifing him.

And from there a reign of madness ensues, including but not limited to Cesare’s King-Kongish abduction of Franz’s friend Hannah (Sara Lindsey). Exactly what kind of nefarious scheme are Caligari and Cesare up to? That’s not clear, though the scheme seems to have elements of zombification, and to say more would reveal spoilers.

The Caligari film became famous for its jagged, disorienting visual style, and likewise, a striking aspect of the play is the style it’s presented in. You may at times be unsure what is happening, and this effect may at times be intentional. For openers, the combination of projected film with live acting blurs time and space. In one astounding scene, the friends at the fair buy hot-baked pretzels from a pretzel booth. The pretzel-vendor is projected larger than life on the back wall, apparently in found footage from an old newsreel. As he reaches toward the camera to offer his wares, the actors who are lined up facing him reach out to receive their goodies. Watching the scene, you could’ve sworn they got actual pretzels that way.

Later parts of the play combine discussions of war with grisly war footage. On a peppier note, old film of flapper girls from the 1920s dancing wildly is mixed with a live flapper (Catherine Gowl again) gyrating onstage. Meanwhile, through all this and more, Jay Ball’s script keeps chiming in with allusions to Weimar Germany after World War I, communist Germany after World War II, and possibly America during the runup to what we hope won’t be World War III.

Is the ultimate message that history repeats itself? I don’t know about that. To a large extent, I repeat myself every day, but every day somehow plays out differently. The details are always different. Perhaps the best line from Caligari to quote as a send-off is this one: “If we do not reform our attitudes toward life, we shall find ourselves drawn to the darkness again.”

Under what sort of rule does the oppressed become an oppressor?

Closing Credits and Ticket Info

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is adapted by Jay Ball from the 1920 film written by Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz, and directed by Robert Wiene. Directing the play for Quantum Theatre is Jed Allen Harris. Actors not mentioned by name above are Mark August in multiple roles (including a barrel-wearing nudist!), and Cameron Nickel as Franz and Hannah’s friend Uli. Through November 24 in the theater of the Union Trust Building, 501 Grant St., Downtown. Visit Quantum on the web for tickets and visitor information.

Scenic design is by Yafei Hu, with lighting by C. Todd Brown, sound by Joe Pino, and costumes by Angela Vesco. Joseph Seamens designed the projections and directed photography, with Mark Knobil as cinematographer. Cubby McCrory is technical director, Randy Kovitz is fight director, and Emily Landis takes charge of props. The stage manager is Cory F. Goddard, assisted by Nathan Walter.

Photos: Jason Snyder