Pittsburgh Post-Gazette – During the intermission of “The Winter’s Tale,” two friends told me they were surprised: They hadn’t expected an opera.

And why should they? Quantum Theatre is staging the production, in collaboration with period instrument group Chatham Baroque and dance company Attack Theatre. In a Post-Gazette article previewing the performance, Quantum head Karla Boos said she preferred the term “ultimate piece of theater” to opera.

“It’s a rich and emotional language, the language of music. I’m a believer in opera as ultimate theater,” she said.

I agree, so I’m stealing this one for the operatic genre. Here’s the thing: opera should be the most complex, elaborate, spectacular form of art out there, and this production, which takes place in the 10th floor music hall of the Union Trust Building, often realized those qualities.

The production is a world premiere, commissioned by the Benter Foundation, but the opera’s musical source materials are quite old. The collaborators borrowed instrumental and vocal music by Vivaldi, Handel, Lully, Bach and others, and merged it with Shakespeare’s play. Much of the text and music were shortened or altered, although the plot remains intact, woven with recitative.

The tradition of theaters assembling various pieces of music into a new opera (known as a pasticcio) goes back to the 17th century, and composers such as Vivaldi, Handel and Haydn contributed to such hodgepodge operas. While the practice largely died out, four years ago the Metropolitan Opera produced Jeremy Sams’ pasticcio “The Enchanted Island,” which set two Shakespearian plays to baroque music.

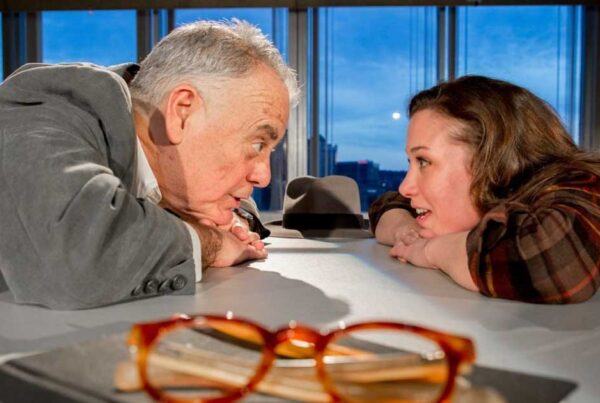

“The Winter’s Tale” is good material for an opera. It scales the extremes of Shakespearian tragedy (a la Verdi’s “Otello” or “Macbeth”) while maintaining a fantastical quality and happy ending befitting a Mozart comedy. King Leontes (David Newman) develops an unfounded jealousy of Queen Hermione (Raquel Winnica Young) that has ruinous outcomes for their family and destroys his friendship with Polixenes, the King of Bohemia (Robert Frankenberry). When a passionate love blossoms between the kings’ children, Florizel and Perdita (who, abandoned by Leontes, was raised by a shepherdess), the two sides have a chance to reconcile. The performance called for 11 singers and a period instrument orchestra of 10.

The visual production was anchored by Joseph Seamans’ video projections, which turned a curtain behind the action into an animated dramatic vehicle, full of swirling paintings, clocks and a shower of flower pedals. The shadows on the two-dimensional surface became characters unto themselves, on a couple of occasions literally so.

Holes cut into different parts of the curtain became host to the faces of choristers. Four Attack Theatre dancers, whose modern style contrasted with the baroque, joined the drama, whether impersonating the passage of time or flogging a remorseful Leontes with a fantastic prop rose. Susan Tsu’s costumes were fresh, elaborate and era appropriate. If anything, there was so much going on in this production that at times it was hard to find a focal point. Andres Cladera conducted the lucid orchestra, whose wrinkles of tempo should be ironed out in future performances.

The singing was the evening’s least consistent component. At one end of the spectrum was countertenor Andrey Nemzer, as Autolycus, whose second-act appearance elevated the entire production. He took more risks than the rest of the cast in terms of trills and ornamentation, while maintaining control of his smooth falsetto and musical intent.

Mr. Newman marked his Leontes with cutting diction that hinted at the character’s internal woes, and his tone had dark, buzzy shadings in “Go, play boy, play!” (set to Handel’s “Arm, arm ye brave”). The voice of tenor Cosmo Clemens, as the clown, had a sweet purity, and soprano Katy Williams made for an energetic shepherdess. Dan Kempson, playing Florizel, was one of the more musical performers, and his noble baritone typified the pride of a young love. Soprano Shannon Kessler Dooley had a ringing tone in the pants role of Camillo.

Few others distinguished themselves as well, and because the arias were distributed among the characters, the singing made less of an impact than the other aspects of the production. No, the real star of the evening was the production, and the opera itself, which made a strong case for a revival of the pasticcio…