Pittsburgh Quarterly – Risky theatre in an old warehouse.

Just as Colette could say, “There are no ordinary cats,” one could say that there are no ordinary productions from Quantum Theatre. “Collaborators,” the 2011 play by John Hodge (who also wrote the adaptation of the film, “Trainspotting”) is violently alive in a way so few new plays are these days, merging comedy and pathos with history and fantasy, and taking risks that are not afraid to challenge some of our more delicate theatrical conventions.

Staged in an abandoned warehouse rumored to have been an abattoir—the iconoclastic drama theorist Antonin Artaud would have loved this—and without built-in heating or lighting, the show has that gritty feeling of 1970s cinematography, as if the air is dirty with earnestness.

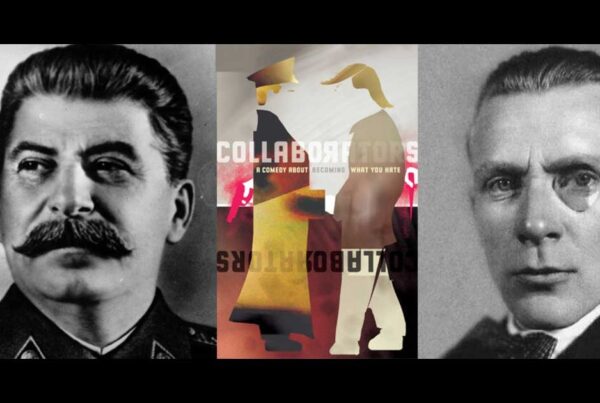

Surreal would be the easiest word to describe this play, but on a deeper level, it’s really Kafkaesque. Hodge transmogrifies the actual but distant relationship between the brilliant pre-WWII Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov (author of “The Master and Margarita”) and Joseph Stalin, into a daring fantasy in which the two men literally switch rolls and assume each other’s jobs: Stalin writing a play, and Bulgakov running the Soviet Union’s vast bureaucracy.

The first act—from the opening sequence, in which a manic Stalin appears from Bulgakov’s wardrobe clutching a typewriter, and then chases him like a Keystone Cop, to the rousing closing song—is a tour de force. It’s as if this first-time playwright threw in every dramatic device he could think of. But director Jed Allen Harris keeps the action fluid by cutting away all the pedantic, connective tissue between scenes, which is, to anyone who watches many plays, such a joyous relief. If only more young directors and playwrights did this.

C. Todd Brown manipulates the lighting like a particle physicist, drawing the audience’s attention from one area of the performance space to another in overlapping scenes. The effect reminded me of the comment in Artaud’s famous essay, “The Theatre of Cruelty,” that the audience should be seated “in swiveling chairs allowing them to follow the show taking place around them.” Although Quantum’s seats did not swivel, the staging flowed back and forth so rhythmically that it felt as if they did.

Tony Bingham infuses the role of Bulgakov with a moment-by-moment consciousness that seems true to the nature of a writer engaged in the minute observation of his world. Bingham’s acting style is so relaxed and uncontrived that it seems at any moment he might wander into the audience and take a seat, just to gain a new perspective on what’s going on around him.

Martin L. Giles as Stalin also avoids any tendentiousness. His portrayal of the brutal Soviet dictator is sumptuously organic—at times comic and at times ugly. He cracks away the plaster of the impression we have of him, creating a character that can project human sensitivity, even if he is unable to feel such sensitivity himself.

John Shepard, as the Doctor, conveys a macabre insouciance that would be very much at home in Kafka’s “The Trial,” while Dana Hardy (Yelena), Ken Bolden (Vladimir), and Jonathan Visser (Grigory) also offer strong performances.

The second act takes on a different velocity from the first, with less energy and more (often preachy) dialogue, as if the playwright suddenly realized he better throw in some dramatic ballast. Especially with a monster like Stalin (and in this politically sensitive age) one wouldn’t want to be accused of writing a farce like “Springtime for Hitler.”

Special mention should be made of Joe Pino’s sound designs. It’s not easy to make a gunshot sound authentic, nor make a Victrola sound like it’s actually playing, moreover in a primitive theatrical setting. Speaking of which, as an old warehouse, the building in which the production occurs is very cold and, although somewhat uncomfortable, adds a sense of metaphoric appropriateness to the historical setting and subject matter of this play. (And I don’t think Quantum is happy unless their rest room facilities—in this case Porta-Potties—are one step short of an Outward Bound experience).

But all of this adds up to an exciting, daring, and wonderfully risky night of theatre, where the writing, acting, and setting converge to create an experience quite out of the ordinary. And such a collaboration is all too rare these days…