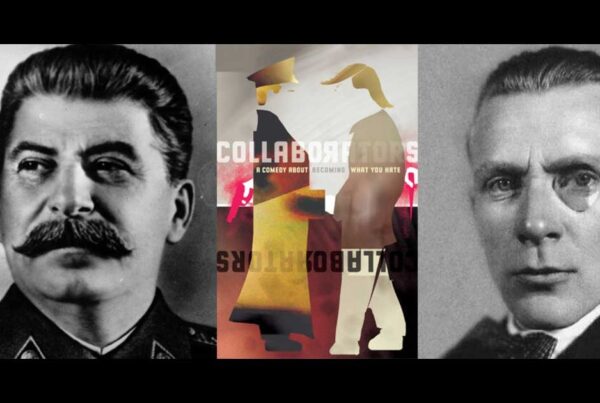

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette – Whizz! Bang! It’s off to the races with a comic chase scene, our hero pursued by an unmistakable Josef Stalin, one of the all-time monsters in the Hall of Despots, trying to brain him with his own typewriter.

Such are the nightmares of Mikhail Bulgakov, a novelist/playwright suffering from ailments and oppressions both physical and political, real and (perhaps) imagined. Awake, his life is equally hilarious and distressed, in a country and at a time where the surreal is normal and the normal intolerable, Stalin’s 1930s Russia, where everyone is equal, until they aren’t.

Bulgakov has a devoted wife, others with whom they share Spartan rooms, and colleagues at the theater where he works. His unproduced play about Moliere, struggling against French royal tyranny, has been banned, because it has been seen as a covert attack (as it is) on Stalin’s tyranny.

Enter Vladimir, a not-so-secret agent of the state, who wants Bulgakov to write a celebratory play for Stalin’s 60th birthday! More ludicrous and terrifying, Stalin wants to help, because, like most psychopathic tyrants of a “scientific” bent, he really wants to be an artist. So the secret collaboration begins.

And playwright John Hodge (in the news these days as screenwriter of “T2 Trainspotting,” the sequel to his own 1996 “Trainspotting”), abetted by the imaginative hand of director Jed Allen Harris, screws the resulting absurdities to a high comic pitch.

Meanwhile, Bulgakov is suffering from some dire illness — terror within farce within noir, or call it multiple crises wrapped in a continuing catastrophe. It all comes crashing down on him in Act 2, which could almost be a different play, but of course it has been inevitable all along. This isn’t Disney.

How much of the story is real? Yes, Bulgakov did write a play about young Stalin, but “Collaborators” is largely fiction, which is to say truthful in its own way, as theater can be. It’s a bitterly convincing parable of a good man corrupted by small comforts and proximity to power.

“I can wield this power with compassion,” he thinks, as doubtless would we, in his place.

But power is zero-sum. As Stalin types happily away on his biographical pageant, Bulgakov discovers that power corrupts, no matter how kindly wielded. These grim truths accumulate in Act 2, driving Bulgakov into impossible contortions of intellect and emotion, and us along with him.

Even as dark thoughts hover in the wings in Act 1 and crowd upon us in Act 2, we are constantly enchanted by the high spirits and satiric effervescence of Mr. Harris’ staging and the energetic exertions of the cast. These are Russians, after all, geniuses of schemes of survival. Until they aren’t.

High among Mr. Harris’ achievements is his casting, starting with Tony Bingham as the decent, bewildered Bulgakov, a sweet-tempered, underplayed everyman also able to hop the comic express when required. As his antagonist, Martin Giles plays Stalin as a terrifying mix of giddy truant and imperious autocrat — and which will emerge at any moment?

They are just two of a cast of 11, playing two dozen roles. Dana Hardy as Bulgakov’s wife and Ken Bolden as the spy are estimable in the largest supporting roles, but there are many others to enjoy: Jonathan Visser’s hapless young playwright, John Shepard’s blood-stained, horny doctor, Mark Stevenson, and Olivia Vadnais as an elderly couple connecting back to the days of the Czar, Dylan Marquis Meyers as Young Stalin. Actually, I’m not entirely sure just who played some of the delicious nuggets here and there.

And did I say this is a Quantum Theatre production, staged (of course) in an evocatively rough warehouse, this one out behind Bakery Square in Larimer (aka Greater East Liberty)? So of course it has skilled designers: Narelle Sissons, whose set seems almost accidental but boasts clever details; Susan Tsu’s costumes; and C. Todd Brown’s lights and Joe Pino’s sound, which help turn one space into many.

How did Quantum get the rights to stage this play, which won the 2012 Olivier Award (London’s Tony)? It leaves us with the more-than-disquieting thought that in spite of the assurances of middle school civics, despotism may actually be the default mode.