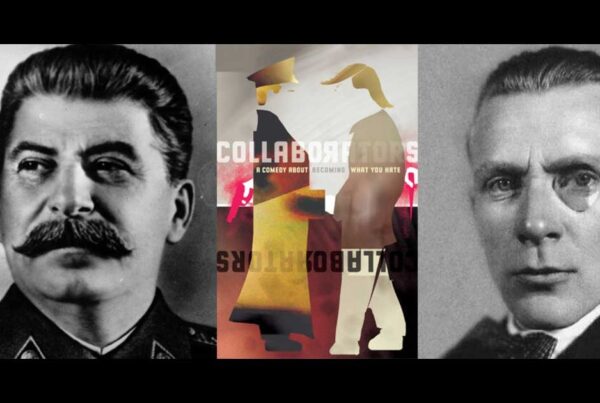

Entertainment Central Pittsburgh – Collaborators, currently at Quantum Theatre, is by the British writer John Hodge. He is best known as the screenwriter for the two Trainspotting movies, and this play is another piece that works by virtue of its grisly seriocomic appeal, though it is grisly in a different time period and with strong references to historical fact.

If you’re going, it may help to know at least a few things about the Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov, so here’s a quick primer.

The Man Behind the Story

Bulgakov (1891-1940) might be little remembered today if not for a novel published long after his death. The Master and Margarita is a surreal satire in which Satan and his crew of hell-raisers visit Soviet Russia. There’s a subplot dealing with Pilate’s interrogation of Jesus, and the whole thing strays rather far from being an uplifting tale of proletarian heroes inspired by Marxist-Leninist doctrine, so it was a poor candidate for seeing the light of day in the USSR under Stalin.

Bulgakov’s widow Yelena kept the manuscript, pushing for publication until well into old age. And when The Master and Margarita finally made it to print in the late 1960s—first in Russian, then quickly in English, French, and other languages—it became a literary hit. Salman Rushdie cited the book as an inspiration for his The Satanic Verses, which likewise includes a historical religious subplot. Harry Potter fans may be interested to know that actor Daniel Radcliffe called The Master and Margarita his favorite novel.

The Master and Margarita still awaits a proper adaptation for stage or screen. Meanwhile, British writer Hodge has based Collaborators on the story of Bulgakov’s life, which was bizarre in its own right.

Bulgakov, who’d been a medical doctor, turned to writing in 1919. This meant he launched his career in the early days of Russian communism—the Bolsheviks had taken power in the Red October revolution of 1917—and though young Bulgakov was not a front-line dissenter, his writings were weird in ways that invited ideological suspicion. (A dark sci-fi comedy about technology misused to turn a dog into a human? That wouldn’t be a commentary on the government’s efforts to create a “new Soviet man” through cultural and industrial transformation, would it? Censors of the 1920s thought so, and The Heart of a Dog got a thumbs-down.)

Before long Bulgakov found himself living in artistic Purgatory. His work was witty and popular, but most of it was deemed too subversive to fly. Weirder yet, one of his admirers was none other than Joseph Stalin, whose aegis almost surely saved Bulgakov from arrest or execution, but did not extend to letting him publish books or have plays produced at will. The dictator kept his pets on a short leash. By the 1930s the writer was a muzzled dog, bucking restraint while forbidden to bare his fangs…