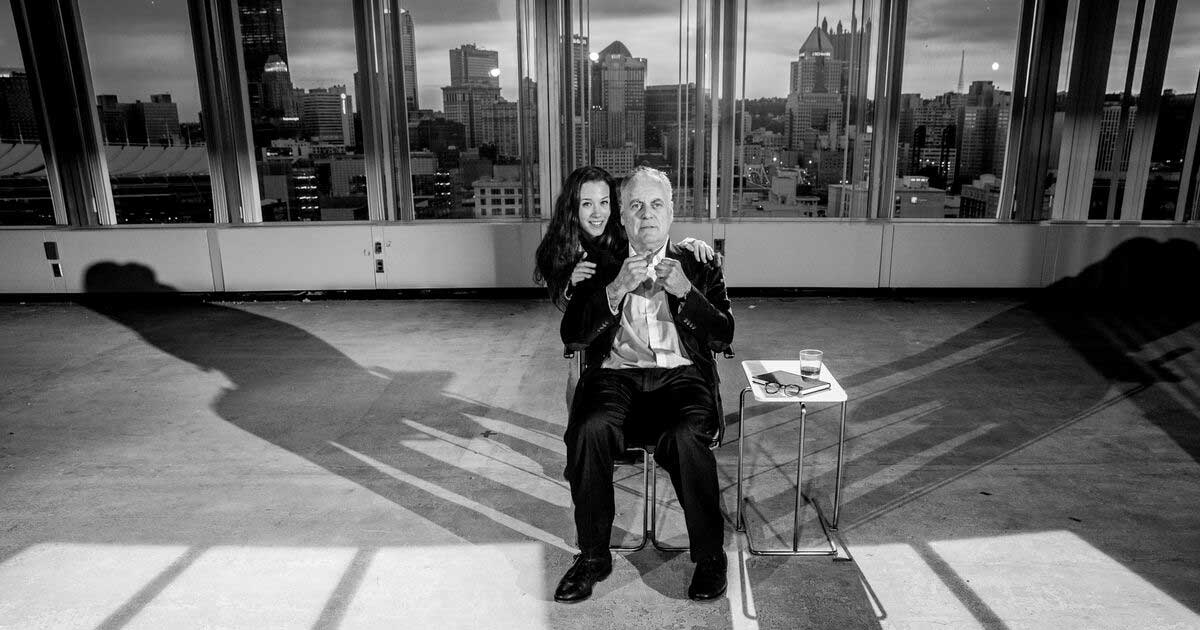

The Pittsburgh Tatler – You take the elevator to the ninth floor of the Allegheny Center and enter into a vast, empty concrete space with floor to ceiling windows and a 360 degree view that encompasses downtown Pittsburgh and its surrounding neighborhoods. Walking around the room, past small tableaus of midcentury furniture illuminated like museum objects in squares of bright light, you see the history of twentieth century urban architecture spilling out below you. And as dusk falls and you take your seat, the city lights up to form a backdrop that, at first glance, seems completely a propos.

Halvard Solness (John Shepard), the “master builder” of the play’s title, is a visionary who once specialized in designing and building towers and churches; now, he’s at the height of his career and can pick and choose the homebuilding projects he’ll deign to grace with his genius. He’s also discovered, in late middle age, that his thoughts sometimes uncannily manifest themselves into reality: he merely needs to imagine, for example, that his apprentice Ragnar Brovik’s (Thomas Constantine Moore) desirable young fiancée Kaja (Kelley Trumbull) will become his employee and pliant lover and – poof! – it’s done, without his seeming to have done anything to make it happen. With Ragnar’s fiancée in his thrall, Halvard can keep the younger man from becoming his competition for new business and maintain his position as high-handed ruler of his little self-built fiefdom.

If you know anything about tragedy, you know this is a man who is ripe for a fall. But this being an Ibsen play, there’s a lot of back story to excavate along the way. Halvard’s fame and success, it turns out, rose Phoenix-like out of the ashes of his wife Aline’s childhood home, which burned down in a fire over a decade earlier and left him with a large plot of land to build his architectural legacy upon. But that fire also led to the deaths of his two young children, and turned Aline (Catherine Moore) into a walking ghost. Now at the zenith of his career, Halvard is paranoid about being overtaken by the next generation and, consequently, fatally susceptible to psychological input that shores up his narcissistic and overweening ambition.

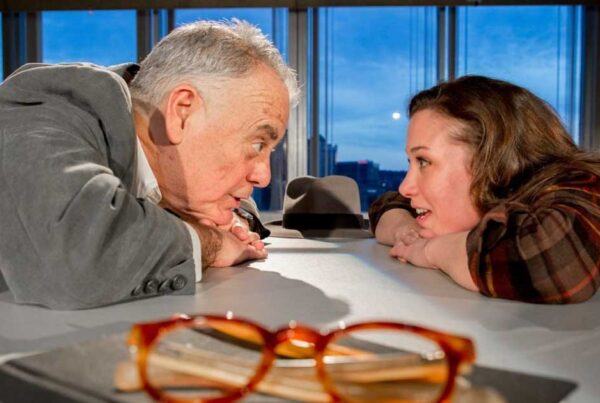

That input comes in the form of Hilda Wangel (Hayley Nielsen), a young woman who had developed a romantic fantasy about Halvard at the age of twelve and who now suddenly appears to collect on a promise she claims he made to her when she was a child. Hilda dredges up memories, as figures from our pasts tend to do, and in conjuring his past self she wills Halvard into behaving like the man she has idealistically fantasized him to be (readers familiar with Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler will see a ready parallel to Hedda’s idealization of Eilert Lovborg – and here, the man’s failure to fulfill the woman’s expectation is also part of the equation). In Halvard’s reaction to Hilda’s dreams of him we witness the complexity of a great man’s great ambitions, and in his shattered family we see the detritus that accumulates in the wake of such ambitions.

The Master Builder is a complicated play, and the Quantum production refuses to make firm decisions about many of the questions the play raises. Is Halvard going a little nuts, as his wife and the doctor suspect, or is he merely caught up in the image of himself that Hilda reflects back to him? Is the play primarily an exploration of character psychology, as the acting style would suggest, or does it want to operate on the level of symbol and allegory, with its textual references to birds and towers and castles? Is this a story of generational comeuppance, or one about past chickens coming home to roost, or the tragedy of a hubristic man? I’m not sure that the production choice to leave the play’s ambiguity on these points unresolved is problematic, but I suspect my own puzzlement about what is at stake contributed to the fact that, when Halvard falls from his own building at the end of the play, I found it difficult to care one way or another about his demise.

Director Martin Giles juxtaposes the formal 19th-century prose of the text with a casual and modern sensibility in the acting, producing a strange clash that shouldn’t work, but really does. Imagine a fashion-forward person who pairs polka dots with plaids and pulls it off, and you’ve got the idea. Giles sets the play in the postwar era, and his staging echoes the formalism of the architecture and furniture design of the era, all clean lines, precise arrangements, and open spaces. Those eloquent objects artfully arranged around the room (Tony Ferrieri gets credit for the carefully curated midcentury modern pieces) are smoothly wheeled in during intermissions to serve as set pieces, giving the impression of a space that lacks clear boundaries between outside and inside, much like Halvard’s mind in the play. Alex Stevens’s lighting design – gamely overcoming the challenge of a very low ceiling – underscores the cool formality of the staging, while Richard Parsakian’s costumes trap characters in several stages of the trajectory to modernity, from Aline’s stiffly formal and almost Victorian mourning garb to Hilda’s late 1950s dungarees.

A lot of psychological depth is mined from this play by the acting ensemble, especially by John Shepard, who finds nuance and surprise at every turn and does a terrific job in a role for which he’s not well suited physically (he has too friendly a natural demeanor for the formidable and quixotic Halvard). But as much as I liked both the setting for the play and the directorial approach, they also seemed at odds with each other: the twinkling city and its evocation of the dreams and accomplishments of master builders past and present felt too large and distant a landscape for the psychological crisis that seemed to be the focus of the production.