The Pittsburgh Tatler – The new adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale into a baroque opera by Karla Boos of Quantum Theatre, Patty Halverson, Scott Pauley, and Andrew Fouts of Chatham Baroque, and Michelle de la Reza and Peter Kope of Attack Theater is one of the most impressive and remarkable collaborative achievements I’ve seen here in Pittsburgh. To create this work, the team collaged together a grab bag of music from baroque composers (primarily Handel, Purcell, Vivaldi, Bach, and Lully) and condensed Shakespeare’s text to fit the structure and meter of the music. The result is a captivating – if not in every aspect wholly successful – mashup of a contemporary sensibility with a baroque-operatic one.

The story of The Winter’s Tale lends itself readily to operatic treatment. It’s a tale of jealousy, loss, and redemption: Sicilian King Leontes (David Newman), suspecting his wife Hermione (Raquel Winnica Young) of having committed adultery with his best friend Polixenes (Robert Frankenberry), orders his man Camillo (Shannon Kessler Dooley) to murder Polixenes. Camillo – recognizing that Leontes’ jealousy is lunatic, warns Polixenes instead, and flees with him back to Bohemia. Leontes interprets their flight as confirmation of Polixenes’ guilt, and imprisons Hermione, who gives birth to a daughter in jail. Her woman, Paulina (Gail Novak Mosites) brings the baby to Leontes in hopes that seeing his daughter will bring him to his senses, but instead he commands Paulina’s husband Antigonus (Eugene Perry) to take the infant and abandon it in some far off place. Leontes puts Hermione on trial, and an oracle arrives proclaiming her innocence; but news of the death of their son, Mamilius, causes Hermione to collapse in grief. She is carried out, and soon after Paulina returns to announce that Hermione is dead. Meanwhile, Antigonus has delivered the baby to the shores of Bohemia, where he abandons her with a bag of gold before being torn apart by a bear. The baby is found by a Shepherdess (Katy Williams) and her son (Cosmo Clemens); they raise the girl, Perdita (Rebecca Belczyk) as part of their family, and she grows up to capture the heart of the Bohemian Prince Florizel (Dan Kempson) son of – quel coincidence! – Polixenes. When Polixenes rejects Perdita as a future daughter-in-law, Camillo advises them to elope to Sicily; Polixenes, the Shepherdess, and her son follow, and in the end not only is Leontes reunited with his long-lost daughter, but Hermione is also brought “back to life” by a trick on the part of Paulina.

Most of this story is clearly told in this ambitious production despite the fact that only a fraction of Shakespeare’s original text is conveyed in the libretto. There are a couple of places where excisions make the narrative a little hard to follow – in particular, toward the end, the explanation of how Perdita’s true identity was revealed to her father is not only confusing, but also overwhelmed by being set to the most familiar music of the evening, Vivaldi’s Spring. Susan Tsu’s magnificently rich and detailed costumes play a major role in keeping the storytelling clear; they are the primary means by which the production establishes the when and the where of the play on Tony Ferrieri’s sparse set, which, in its poverty of elements, is reminiscent of the historical reconstruction of a baroque stage from films like Amadeus or Molière. Indeed, the scenic design serves primarily as a surface for Joseph Seamans’ witty, playful, and engaging projections, which sometimes function to establish the scene (as in a wonderful, Monty Python-esque moment in which two-dimensional images of the ocean and a ship are layered and animated in a way that replicates the use of moving cutout two-dimensional flats for special effects on the baroque stage) and sometimes serve as a choreographic partner to the four superb modern dancers (Kaitlin Dann, Dane Toney, Anthony Williams, and Ashley Williams) who weave continually through the action. The projections also provide a strong element of whimsy: when singers poke their heads through the curtain, they become the animated center of projected flowers or roccoco decorative elements, and during the love scene grotesquely enormous flowers provide a clever visual pun on the association of flowers with female sexuality.

These delightful visual elements – the costumes, the projections, and the choreography – go a long way toward ameliorating the inertia that threatens when the libretto becomes repetitive, as librettos in operas tend to do. And there is a lot of repetition of lyrics here, which is perfectly understandable from the point of view of the structure of song, but a little baffling when you consider how much more of Shakespeare’s language might have been included if the collaborators had felt themselves a bit less beholden to the song structure’s demand for repetition.

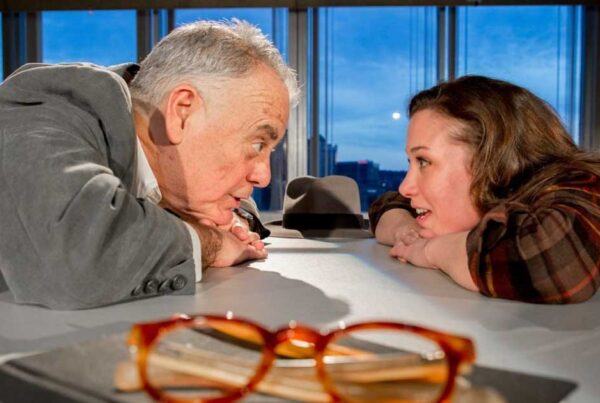

Of course, opera is not only (or, as I keep learning, even mainly) about storytelling; it’s first and foremost a musical art, and on that score (pun intended) The Winter’s Tale has a lot to offer. All of the members of the ensemble deliver strong vocal performances, and a number of them are outstanding actors as well. In particular, Newman is intense and fiery as Leontes, and Katy Williams and Cosmo Clemens are charismatic as the Shepherdess and Clown. Countertenor Andrey Nemzer has a couple of showstopping moments as the rogue Autolycus who dupes the peasants, and Belczyk and Kempson are charming as the young lovers. Under the sensitive direction of Andres Cladera, the music is beautifully performed by a small orchestra featuring the three members of Chatham Baroque (Halverson on Viola da Gamba, Fouts on Violin, and Pauley on Theorbo) along with seven other masterful musicians playing historically appropriate instruments…