Pittsburgh Post-Gazette – A room with a view is a wonderful perk, but as a backdrop, it can be a distraction or, worse, competition for a work such as “The Master Builder.” The play by Henrik Ibsen boasts themes enough for a skyscraper full of dramas, with regret on one floor, guilt on the next, and then destiny, and luck, and so on toward the clouds — about where you will find Quantum Theatre perched these days.

Stunning vistas serve as a complement to the sharp interpretation and keen performances playing out on the ninth floor of the new Nova Place, the building at 2 Allegheny Center where the four-sided views can be breathtaking in daylight, or a dark skyline dotted with sparkles, as it was when night fell for Friday’s opening performance.

The late 19th-century work here is set at a time in the 20th century when an older man might still wear a fedora and a young woman can wear a flannel shirt and jeans and not be scandalized. It also is a time when many of the buildings that are visible over the actors’ shoulders were first making their marks on the Pittsburgh skyline.

It’s a setting perfectly suited to “The Master Builder,” a play that “moves almost everywhere between the everyday and the sublime,” as it has been described by Oscar and Tony nominee David Hare, who recently created a new translation for the Old Vic.

Ibsen rolls his myriad ideas into the lives of people who have been rewired by singular events that sent them hurtling down their current paths.

John Shepard, an actor, educator and the director of Quantum’s brilliant “Tamara” last year, has the title role of a man hovering between control and madness. When we meet his Halvard Solness, the master builder of all he surveys, he is a lech who has mesmerized his much younger bookkeeper. Youth is ever on his mind — to seduce or be seduced by young women or to suppress an up-and-comer in his field.

The idea of youth at the door — as inspiration or usurper — is one of the threads that runs through “The Master Builder.” So is luck, good and bad.

People are often telling Solness how lucky he is, but we learn that he has paid a terrible price for it. He has realized his dream of becoming a builder of “homes for human beings” from the ashes of a devastating fire. The family tragedy has sucked the life out of his mournful wife, Aline (Catherine Moore), who despite her husband’s roving eye remains dutiful. Both Solness and Aline worry that he is giving in to what he describes as the trolls and demons eating at his soul.

Solness, who views his distant wife as an unrealized vessel of potential, is worried about more than just his soul. He fears his ambitious assistant, Ragnar (Carnegie Mellon University alumnus Thomas Constantine Moore), will pull the rug out from under him as Solness did to Ragnar’s dying father (John Reilly). Ragnar’s fiancee, Kaja (Kelly Trumbull), is the infatuated employee whose life has been upended by her feelings for Solness.

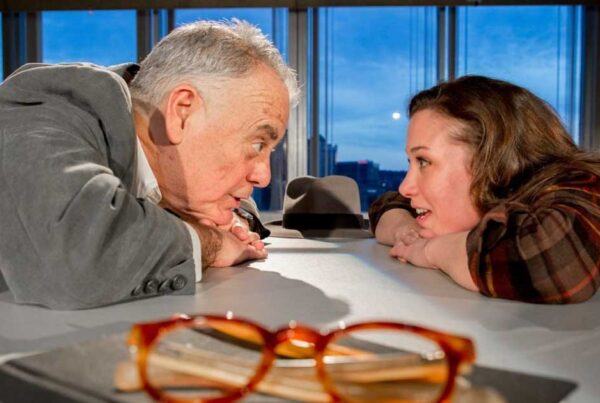

Into this sea of turbulence marches Hilda Wangel (Hayley Nielsen), a 23-year-old who has been stuck in time from the moment she met Solness a decade earlier. She had watched enraptured as he climbed to the top of a church steeple he had designed and placed a wreath on it. Later, at her parents’ home, he stole a kiss from her and promised to build her a kingdom of her own.

Ms. Nielsen as Hilda is youth personified as she comes knocking at the door, with the intent to collect on Solness’ long-ago promise. She is living in a fantasy world, perhaps as mad as he is. But now it is his turn to be infatuated. The man we first met, who could cheat on his grieving wife and deny a father’s dying wish, can deny this girl nothing.

Will she be his saving grace? He certainly thinks there is a chance that this girl might be his salvation. Even Aline and her confidante, Dr. Herdal (Philip Winters), are hopeful she can shine a light through the darkness of their lives.

Under Martin Giles’ direction and with a solid cast led by Mr. Shepard, Ibsen’s revelations pile up with as much restraint as the over-the-top situations allow. In the first act, especially, there is humor to be found in a look or gesture, with the punctuation most often provided by a bolt of knowledge or a jolt of irony.

Tony Ferrieri’s scenic design, likewise, is spare and serves more to suggest an office, a home or a garden. Some set pieces are mobile, taking temporary space in the windowed horseshoe that leads to and from the staging area. Don’t be intimidated by a play in three acts -— you are encouraged to spend time in all the space that is now under Quantum’s spell.

From the stage, as the actors look into the distance and talk of high-steepled churches and castles in the air, the names of places they describe are Norwegian, but what may be seen by night are sites that glow, such as St. Mary of the Mount Church on Mount Washington and the changing art installation atop Penn Avenue Place.

The lighting inside by Alex Stevens includes moments at the end of each act, in which the face of the last speaker suddenly is frozen in a bluish light that fades a split second after the overall lights fade to black. That haunting effect stays with me, along with the glow of Pittsburgh’s castles in the air…