Entertainment Central Pittsburgh – Strange voices speak in Henrik Ibsen’s play The Master Builder. On the night I saw Quantum Theatre’s new production, one of the strangest came from a young woman in the audience. She succinctly summed up the insidious allure of the play—and why you should see it—better than I could hope to.

It happened during the post-show talk-back, when the director and actors sat on stage and responded to questions and comments. Talk-backs aren’t held often, and patrons with painful memories of classroom discussions tend to flee them, but this one hummed along nicely. The Master Builder is a play that can set your mind spinning on more levels than you knew it had.

There were director Martin Giles and his cast members, bantering nonstop with a Sunday-evening crowd dominated by middle-aged and older folks. It was the sort of audience that you’d expect to relate strongly to The Master Builder, since the title character is an aging architect embroiled in late-life crises—including dangerous liaisons with women young enough to be his daughters.

A few women of that description happened to be in attendance, and finally one of them chimed in. Using just 20 words—brief enough to tweet, yet loaded with paradox—she said what she loved about the play:

“As a younger person, I thought it was totally relevant. I identified with every character. And I hated them all.”

To elaborate: The woman recognized aspects of herself in each of Ibsen’s characters, from the old megalomaniac and his Witch-of-the West wife to the youthful strivers. Many of the aspects aren’t pretty. But they are artfully woven, and it’s fascinating to watch the story unfold.

Bats in the Conning Tower

Ibsen set The Master Builder in Norway during the 1890s, though Quantum’s production updates it to the mid-20th century. The company is using a 1978 translation by Rolf Fjelde, a renowned American Ibsen scholar who gave the language a smoothly modern feel, which the actors preserve by not attempting stuffy accents.

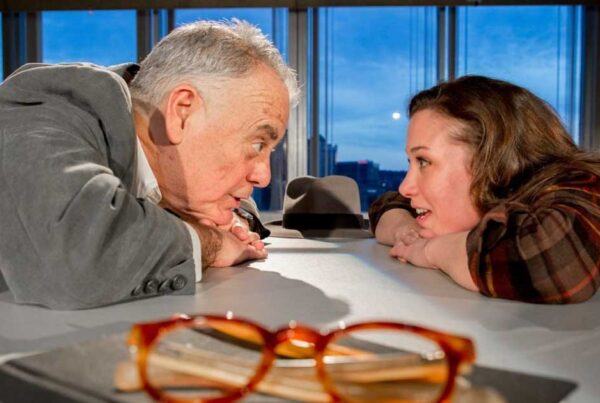

The play hits the ground running. When master builder Halvard Solness (played by John Shepard) breezes into his architecture office, he quickly proves to be a frightening hybrid—a tyrannical businessman with a malignant artist’s ego.

Solness brutally badgers his chief assistant, the elderly Knut Brovik (John Reilly). He refuses to let Brovik’s son Ragnar (Thomas Constantine Moore) take the lead on a building project, even though the young man has drawn up promising designs. Ragnar’s girlfriend is the office bookkeeper, Kaja Fosli (pronounced “Kaya” and played by Kelly Trumbull), with whom Solness is having an affair.

And that is only the opening scene. Soon we meet Solness’ unhappy spouse, Aline (Catherine Moore), who is rigid and frigid but sharp as a hawk. Then comes the woman who has been compared by some theater critics to a grown-up Lolita: the mysterious Hilda Wangel (Hayley Nielsen).

This aspiring young femme fatale arrives unexpected and unannounced. Hilda claims to have met the master builder a decade ago, when, as a girl of 12, she was enthralled by the great man. Doesn’t Solness recall how he showered her with mischievous kisses, promising to build a kingdom where she would reign as princess? Now she has come to collect.

From there The Master Builder escalates—or perhaps more accurately, descends—into widening spirals of madness. And the play’s genius is in how keenly the pandemonium is portrayed.

It’s common today to quote Jean-Paul Sartre’s dictum “Hell is other people,” but Ibsen reminds us that the problem runs deeper. The sly Norwegian playwright knew that chaos does not arise from perfectly reasonable persons (the kind we like to think we are) having to deal with the battiness of others. We’ve all got bats in our belfries that constantly flap around, emitting their hypersonic hoots and disturbing defecations. No wonder all Hell breaks loose when we take them out to meet other people’s.

The Master Builder depicts these processes with uncanny precision. Layers of desire and delusion pile up, while the characters’ dirty under-coatings are peeled back.

Psychobabble and Fright-House Mirrors

To illustrate how crazy the predicaments are—and how deeply they reflect the characters’ inner craziness—let’s sample a farcical exchange from an early scene. Solness is chatting with the family physician, Dr. Herdal (Philip Winters), who probes into sensitive territory by pointing out the obvious: Solness’ wife is angry. She has noticed that her husband seems to have an unseemly interest in Kaja the bookkeeper.

Solness denies it, spinning a web of half-true fabrications, then twisting the bullshit into psychological bat-shit. He explains why he allows his wife to wrongly suspect him of what, in fact, she has every right to suspect:

Solness: “I feel that there is almost a beneficial kind of self-torment in letting Aline do me an injustice.”

Dr. Herdal: “I don’t understand a word of this.”

Solness: “Yes! Don’t you see? It’s like making a small payment on a boundless, incalculable debt to your wife. And then it eases the mind a bit. And you get to breathe more freely for a while, you know?

Dr. Herdal: “God help me if I understand a word.”

Coming early in the play, those are laugh lines. But the laughter dissolves to a spooky chill as the story progresses. Gradually we learn that there is more to Solness’ philandering (and his wife’s bitterness). Weird counter-themes emerge as dreadful truths are revealed while Solness and his muse, Hilda, share ecstatic visions of the “castles in the sky” they plan to build. The whole thing becomes a maze of fright-house mirrors. And as director Giles noted with a grim laugh at the talk-back, “You know it won’t have a happy ending.”

A Venture into Upper Space

The Master Builder premiered in 1893 and has received ongoing worldwide analysis by critics, but not many theater companies have performed it. We’re fortunate to have Quantum present it here…