Springboard Exchange – Pittsburgh’s Quantum Theatre is an experimental, site-specific theatre company currently celebrating its 25th season. Founded by Artistic Director Karla Boos in 1990, the one hard-and-fast dictum that defines the company is that they create theatre in places that are not theaters.

Boos was in Los Angeles attending CalArts and knew she wanted to make unusual and experimental theatre, but also knew that she didn’t know how L.A. worked or how she would do it there. She had memories of Pittsburgh from her undergraduate days of it being a “contained, solid, warm sort of city,” and thought that the sort of theatre she wanted to make would be different than anything else already there.

“I was influenced by a much more global perspective,” she says. “That was a part of my training at CalArts. There were artists from all over the world there experimenting with different forms. I thought that would be new here and decided to start that to see if it would be meaningful.”

Within two weeks of returning to Pittsburgh to launch Quantum Theatre, she had a meeting with the Vice President of Creativity and Senior Program Director for the Heinz Endowments, Janet Sarbaugh, and after that she had a grant to get started.

From the very beginning, Boos says, Quantum Theatre was about experimentation. “We were trying to make theatre that was relevant, and trying to not make any assumptions about how theater works but ask questions about what might make it more meaningful.”

While there are several ways in which Quantum Theatre utilizes experimental practices, Boos says they often experiment with the language of theatre: staging works that might include a contemporary opera entirely in Spanish or a play by a 19th-century Norwegian playwright known for his minimalist approach to words (Henrik Ibsen, specifically, and we’ll get back to that).

“We look globally for artists and writers who are like-minded in the ways they might want to experiment,” says Boos. “The sky is the limit in terms of what we’ve done, but all of these works have been in places that aren’t theaters. We never wanted to return to the confines of the theatre. We find the place we are in to be an endless contributor to what we are making.”

Toying with the concepts of language and communication is a large component of their experimentation. For example, a theatre company that stages a Shakespeare work might wildly reimagine the setting and costumes while still retaining the sacrosanct Shakespearean dialogue. Quantum Theatre instead uses music as the primary communicator, as they did last fall for their production of The Winter’s Tale.

In this production, staged in collaboration with Chatham Baroque and Attack Theatre inside the 19th-century music hall at the top of the Flemish-Gothic Union Trust Building, the action is set to the best of baroque music (Vivaldi, Handel, Monteverdi) and Shakespeare’s words are set to song with sumptuous set and costume designs to complement the baroque opera theme.

All other forms of experimentation aside, the thing observers most remark upon is the use of non-theatre environments.

Where other theatres might use lighting and projections to convey settings and create moods, Quantum Theatre uses sunsets and the shadows cast by performers on giant hillsides. “The visual landscape is completely open to us,” Boos says. “Everything that comes in through your senses for those two hours of a production contributes to what you take away from it, whether it’s words or music, in English or another language, or what might you be looking at.”

At the point at which a project has moved forward enough that they begin scouting for locations, the director (Boos or someone else) will share his or her vision – perhaps they see great height, or a certain texture becomes apparent, if it is ancient and layered and crumbling. Boos says the vision will be broad stroke at first, then they will go out and attempt to find a location that suits it.

Other factors also come into play when choosing a location.

“We start thinking about what it would be like for the audience to go into certain parts of our city for this particular project,” says Boos. “We try to make partners and deal a lot with our many friends in community development, neighborhood development, and real estate development, so that it’s possible for there to be another layer than just whatever is artistically right for the artist, but also that the theatre experience is about the audience going somewhere they don’t know, or going somewhere familiar and seeing it completely differently. How does our occupation for that short time affect the neighborhood, or does it at all? You work within the limitations and I actually find that empowering.”

Given the nature of their wildly different productions, they cannot work with a core group of company actors, though they do continue to work with people they have built relationships with, especially designers.

“There are some people who are at the top of their fields here, including teachers and students from Carnegie Mellon, who love to work environmentally and within our adventurous aesthetic,” says Boos. Susan Tsu, the costume designer of Winter’s Tale, “has probably never costumed a baroque opera before. Even as grand as her career has been she might have been doing something outside the realm of anything she has done before.” Boos pauses and laughs at her previous statement. “Though I don’t know, maybe she has!”

Boos says she is attracted to things that seem to be a new language for the theatre. When choosing future productions, she says, “I have to find something fascinating about it that I don’t understand and I don’t know anything about. It has to strike me as new, and the project is where I bring an audience inside my process of discovery.”

She recently saw the film Eye in the Sky, a modern war film examining the moral ambiguity of drone technology, and found the language of the film inspiring. “The language is what they see through the eye of the drone. The actual images were the language of the film, and that didn’t exist ten years ago.” The fascination in her voice is readily apparent, so when she says, “Maybe the language of drone-shot footage will be something we use in the future,” you can almost sense that she’s already envisioning it.

Quantum Theatre doesn’t typically repeat any productions. “We can’t go back; we have to go forward,” Boos says firmly. Forward movement is another cornerstone of Quantum Theatre: they have produced 15 world premieres in the last ten years alone. Theirs is a twelve-month season with a new production each quarter, for a total of four per year.

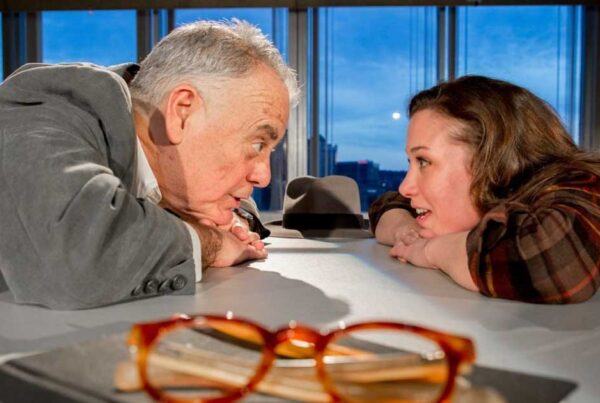

The current season ends soon with the premiere of The Master Builder by Henrik Ibsen, a collaboration with the Heinz Architectural Center at the Carnegie Museum of Art that dovetails with the museum’s ongoing exhibition series celebrating Modernism in Pittsburgh. The production will be staged inside the iconic (and controversial) Modernist building once known as Allegheny Center, now Nova Place, and opens April 8.

In addition to the baroque Shakespeare opera and the Modernist staging of a 19th-century play about a Norwegian architect, this season has also seen the American premiere of a Scottish play (Ciara) and a new work by a development theatre company called Hatch Arts Collective that Quantum Theatre is mentoring (Chickens in the Yard).

After closing the chapter on this 25th year, the “beginning of the next 25 years” starts with an adaptation of Peribáñez y el Comendador de Ocaña, a tragicomedy by Lope de Vega from the early 1600s, directed by the celebrated Chicano theatre-marker Tlaloc Rivas.