The Pittsburgh Tattler – What – or who – is Chatterton?

Well, that depends on how much you trust the historical record, and, I guess, whether you believe anything can be verified by documents at all. The “real” Thomas Chatterton was a historical personage – an 18th-century English poet who committed suicide at the age of 17, after having invented a 15th-century poet, Thomas Rowley, and published a series of “found” poems under that assumed identity. The “fictional” Thomas Chatterton of Quantum Theatre’s adaptation of Peter Ackroyd’s 1987 novel Chatterton is, like his model, a forger of documents, and the trail of fakery he may or may not have left in his wake casts doubt on what seems to be a clear historical record. In this version, even his suicide may have been faked – or accidental – or real – and the same goes for a whole host of poems by later (and greater) poets whose work the fictional (or was it real?) Chatterton may or may not have imitated or forged after he supposedly did or didn’t die.

Are you confused? Complicating things further – for the audience member at least – is that at any given moment in the story you have only a very partial and incomplete picture of any of the three or four story lines that zip past each other and occasionally intersect in the course of a peripatetic three hours. Like Quantum’s 2014 production of Tamara, this production asks the audience to follow the characters through the space, trotting from room to room of the byzantine Trinity Cathedral as the action bounces from time period to time period and story line to story line.

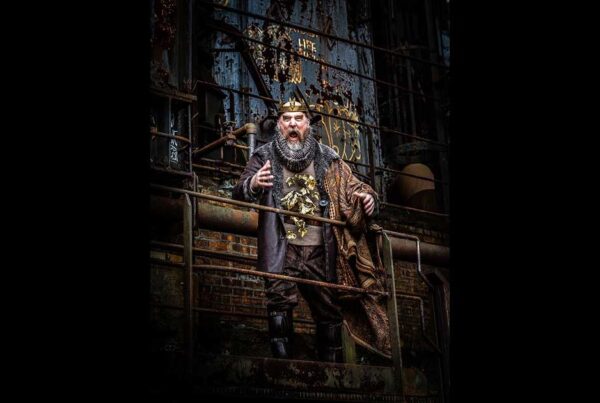

If you start the evening with a quill (as I did), you’ll mostly follow Chatterton (Jonathan Visser) himself as he tells you about his early life and freely confesses his invention of “Rowley” as a means of rising out of Bristolian poverty and establishing himself as a writer and poet. His story line is interrupted by scenes from “the present” (although a present that looks more like 1960 than 2018), in which well-known author Harriet Scrope (Helena Ruoti) has a terrible case of writer’s block and also schemes for reasons that are never completely clear to keep a younger author, Charles Wychwood (Tony Bingham), from cracking the mystery of whether or not Chatterton really committed suicide, and in which Merk (Tim McGeever), the assistant to a recently deceased painter, sells forgeries of that painter’s work to Mr. Leno (Alan Stanford), begging the question – as do Chatterton’s poems – of what constitutes a “real” work of art.

If you start the evening with a typewriter, as my date for the evening did, you spend more time with Scrope, Wychwood, and his friend Philip (Martin Giles) – a librarian, I believe? – and you learn a few secrets about them that we quill-followers weren’t privy to – for example, that Scrope may have plagiarized her first “breakthrough” novel.

And if you start the evening with a pen – well, I can’t tell you what you’ll learn, because unfortunately there wasn’t anyone near me from that track at the (very lovely) dinner that is served around 9 pm, so I wasn’t able to pick their brains about what they experienced while I was chasing after Chatterton and Merk, the art forger (pro tip: go in a group of three and take different tracks – and/or be much more outgoing about grilling your dinner companions than I was!)

Post-dinner, a third time period pulls into view, one in which painter Henry Wallis (Martin Giles) – the 19th-century artist who created a famous painting of Chatterton on his deathbed – convinces poet George Meredith (also a historical figure) to pose as Chatterton for his painting and at the same time falls in love with Meredith’s wife, Mary Ellen (Gayle Pazerski). Pazerski also plays Wychwood’s wife in the present day, who ends up falling in love with Philip after Wychwood dies of some mysterious illness that may have been explained in a track that I was not on.

As you can see from my description, there’s a lot about Chatterton that I can’t describe to you, because even with my partner taking a different track I wasn’t fully able to piece together the whole from its parts. Unlike in Tamara, where you could choose to follow one character through the entire story and thereby glean a full picture of that character’s experience in the world of the play, here the tracks are pre-determined and give you only limited – and frequently obstructed – glimpses of any one character’s journey. This not only makes the story perplexing but also keeps you from connecting to any of the characters – by the time we sat down for dinner almost two hours into the show I still hadn’t found a character whose dilemma I truly cared about.

The sense of ungroundedness to the action is compounded by the space in which the show takes place. A good deal of the action has been staged in the cavernous sanctuary of Trinity Cathedral, where the acoustics render much of the actors’ dialogue unintelligible and it’s not always clear where we are (in the world of the play, that is). Moreover, much as I love the feeling of adventure and scavenger hunt that goes along with scurrying after the actors as they go from scene to scene, it felt, in this case, as if the purpose of our moving from room to room was to replicate a cinematic structure rather than a theatrical adventure.

Nevertheless, there is a lot of ambition behind this production, and the thematic material being worked here feels very much aimed at our present historical moment. I have not read Ackroyd’s novel; I imagine, from this adaptation, that much of its punch and pleasure derives from a deployment of unreliable narration – that is, that as a reader you are constantly having the rug yanked out from underneath you by new information whose veracity is destabilized by your uncertainty about whether or not to trust the source. Writer/director Karla Boos and her writing partner Martin Giles seem, at any rate, to have sought to give their audience that experience of destabilization – we’re never sure who to trust here, or which documents are real, and as we watch characters later in history give credence to documents that scenes from earlier in history demonstrated to have been deliberately forged – or maybe not – we get the impression that the entire edifice on which the historical record rests could be as flimsy as a house of cards. That’s certainly a potent metaphor for the era of so-called “fake news” we currently inhabit.