The Pittsburgh Tatler – While there are several guns conjured to the imagination in EM Lewis’s one-person play The Gun Show (Can we talk about this?), the most frightening moment of the play (for me, at least) doesn’t involve any weapons at all. That moment comes when Andrew William Smith – my colleague at the CMU School of Drama, whom I know to be a reasonable, rational, calm human being – becomes red-faced with fury as he channels conspiracy theorist Alex Jones’s incoherent and illogical rage at the prospect of even the most minor regulation on guns.

That can’t be an easy place for Smith to go. But then there’s nothing easy about this play, which relates five “stories” from the playwright’s own experience with guns, three of which are relatively benign, and two of which are harrowing (no further spoilers here, you are safe to read on). Lewis – who grew up in rural Oregon, and still lives on her family farm – has a lifelong relationship with guns, gun culture, and gun owners, a relationship that was complicated by a tragic event that occurred sixteen years ago and eventually led to the writing of this play. As such, Lewis occupies a fairly unusual position in the conversation on guns: she has lived – and deeply gets – both sides of the debate.

Her doubled understanding of how people feel about guns is mirrored in the play’s structure: Lewis is both on stage – played by Smith – and also in the audience at every performance, observing him narrate her story and silently reacting to its telling. Her presence not only raises the emotional stakes of the play, but also instantiates her primary purpose: in a very real sense, what Lewis has staged here is a dialogue with herself, one that models the kind of nuanced and complicated dialogue she hopes her stories might inspire.

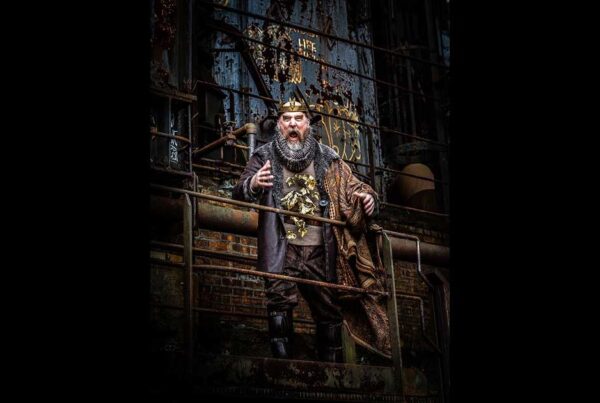

Those stories are compelling, and she heightens their theatricality by peppering her script with cheeky moments of ironic self-awareness. Director Sheila McKenna takes advantage of such metatheatrical moments to provide comedic relief, and under her direction Smith shapes a performance that plays in multiple registers, from light banter with the audience to an intense recreation of a traumatic memory. He also brings equal conviction to each of the script’s shifting and contradictory stances towards guns: it’s clear that he aims to avoid putting his actorly finger on the scale in favor of one side over the other.

A challenge for this play, however, is that it can’t avoid making some assumptions about its audience. For example, at one point Lewis accuses “city dwellers” (like those of us in the Pittsburgh audience?) of being indifferent to the needs of people in rural communities who need guns because they can’t count on law enforcement for protection. Implicit here is a slippery-slope argument that any desire to see some regulation on guns is a desire to make all gun ownership illegal, and as an “urbanite” myself I couldn’t help but feel a tinge of resentment at what felt, to me, like a straw-man setup. Moreover, while the play’s main premise is that conversation has become impossible because of extreme and hardened positions on both sides, that’s something of a false equivalency: despite Jones’s paranoia and the NRA’s propaganda, those who wish to enact common-sense gun regulations do not occupy the same kind of extreme position as those who equate any regulation whatsoever with tyranny and fascism.

Nonetheless, because Lewis’s personal history illuminates many facets, pro and con, of gun culture and gun ownership, her play opens what may be new perspectives and new ways of looking at the problem to people coming from all points on the spectrum. Among the loaded questions she provokes are: Who is really endangered by guns? What is the relationship between guns and security? How do we define “safety”? A talkback after each performance invites audience members to consider those and other questions: the dialogue begins.