Pittsburgh Owlscribe – Quantum Theatre Pittsburgh is now staging a brilliant play by Howard Barker, who gives us a look at a Rebel female painter, Galactica, working in Venice in the 16th century. The powerful Doge is a devotee of paintings and artists and recognizes Galactica’s talent. However, after awarding her a commission to paint a large canvas depicting the Battle of Lepanto, a huge naval battle that saw the coalition of Catholic forces defeat the fleet of the Ottoman Empire in 1571, will their relationship last or are there too many forces at work to sustain it?

In this cleverly written play, there are tensions between personal ambition and moral responsibility seen through the lens of sexual politics. But the playwright defies expectation (you’ll laugh quite a bit) and how you feel at the end is anyone’s guess.

Director Andrew William Smith Photo courtesy Quantum Theatre

What follows below is a Q&A with the play’s director, Andrew William Smith, associate professor of acting at Carnegie-Mellon University.

Q: In your director’s note in the program, you say you owe the place in your life the world of Howard Barker to two mentors, Richard Romagnoli and Cheryl Faraone, who explored the playwright “with such fearlessness that their college-aged students were left indelibly marked.” I assume you were one of their students.

If so, how have you continued to explore Barker’s works? Have you seen many of his plays, and Scenes from an Execution in particular? Did you play a part in Quantum’s decision to produce this play this season?

A: Yes, I was one of their students. I was one of the many generations of students at the Middlebury College Theatre department that they taught and infused with a passion for language, and for theatre that opened up new questions and pushed the audience and artist in addition to entertaining them. I have continued to explore Barker’s work through watching the many productions that these two directors put on, including: The Europeans, The Castle, Victory, among others. I have never been in one, and I have never directed one, so although this writer has been brewing inside of me for decades, I have never had the chance to directly tackle his work – until now.

And yes, I brought the show to Karla Boos and Quantum Theatre. After being in five shows with Quantum as an actor, and witnessing countless others as an audience member, it seemed a good fit with the spirit of Quantum’s work in terms of its stylistic demands and overarching ambition. Karla agreed, and we worked together to find a time to make it all come to life.

Q: This was my first encounter with the playwright, and I must admit I was impressed with his writing, so witty, so dynamic in the way the actors respond to one another with elevated dialogue. Because this is my first look at the playwright’s work, I’d like to hear more from you about his style and things that characterize his work.

A: Barker has coined the term “Theatre of Catastrophe” to describe his work. His plays often explore violence, sexuality, the desire for power, and human motivation underneath all of it. He writes with a visceral energy that is an actor’s dream. His language is dense – not poetic, but powerful, efficient, and extremely specific.

In understanding any writer, it’s important to understand the limits of each script: How much is too much? How little is too little? The play serves as a container for the performance, so how much can this script hold? What I have learned from Barker’s writing is that it can handle an enormous amount of performance. There are no small, subtle characters in this play. His characters are passionate, with fierce beliefs, impulsive and sometimes contradicting behavior with few apologies.

Barker isn’t interested in making things clear or pushing a particular point of view. Rejecting the widespread notion that an audience should share a single response to the events onstage, Barker works to fragment response, forcing each viewer to wrestle with the play alone. He raises potent subjects from a variety of different angles, challenging the audience member to soak it all in and come to their own conclusion, or more accurately…come to their own set of questions in response.

“We must overcome the urge to do things in unison,” he writes. “To chant together, to hum banal tunes together, is not collectivity.” Where other playwrights might clarify a scene, Barker seeks to render it more complex, ambiguous, and unstable.

It has been a fascinating and thoroughly engaging process for all of us.

Q: In painting her commission, the artist Galactia, known for her brilliance, has been described by some as being politically naïve. While that may be true, I felt that she knew of the political backlash her work would cause, but with the zeal of a martyr, went ahead with her original intention for the piece and refused to alter it. Which side of the coin do you favor and why?

A: What a great question, and one that I think Howard Barker himself wants us to ask. The actions of Galactia can be seen as heroic and cunning, or as idiotic and naive. Her character can be seen as being overrun by the political institutions she comes up against, or as taking over these institutions. The play truly offers the possibility of both. My job as a director is create a platform on which this play can be received: heard, seen, and felt with clarity, in all its ambiguous complexity. Our rehearsal process was about digging into every nook and cranny of each argument and allowing it all to come to life in the work of the actors and designers. We had so much to work with! Life has proved itself to be as complicated as Barker’s script sometimes, no matter how much we may yearn for simplicity. There is always another side.

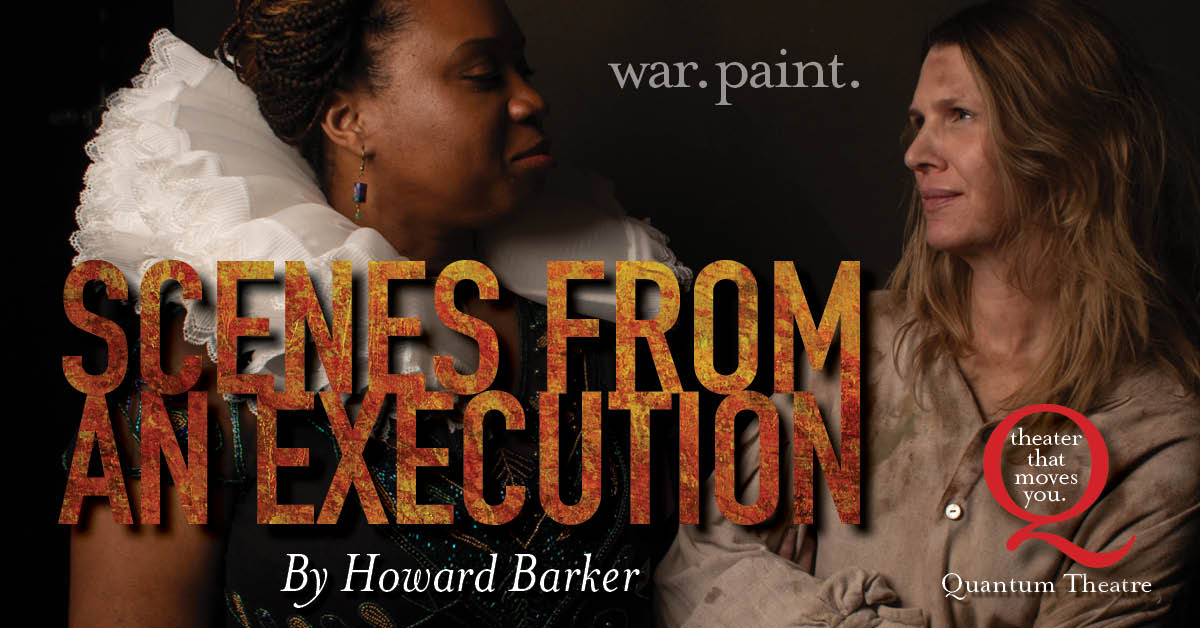

Hansel Tan and Lisa Velten Smith in a scene from ‘Scenes From an Execution’, the Quantum Theatre season finale. (Images: Jason Snyder)

Q: The question of the love affair between Galactia and Carpeta is somewhat muddled in my mind. Several times, we hear characters calling her promiscuous, so I’m wondering about her depth of feeling for Carpeta. By the way, does the name Barker picks for her lover suggest that he’s a mere rug under her feet? And Galactia, as in galaxy, a reference to her immense talent?

Carpeta himself, wavers in his affection. At first, he seems truly enamored, then he betrays her by accepting the new commission after Galactia’s fall from grace. Finally, he secures Galactia’s release from prison after much effort and putting himself in the Doge’s disfavor. How do you see their complex relationship?

A: Galactia and Carpeta believe every word they say about each other and their relationship in the moment that they say it. They are passionate lovers as they fight with a ferocious intellect. They support each other even as they use each other for personal gain. They love each other deeply even when they so actively hurt each other. They are swept away with love, while being filled with doubts.

I think their relationship also speaks to the role of a muse. From where do we draw our inspiration? As the Doge asks in the show: “Why is it, I wonder, the base instinct is so often the spur to fine achievement?” And, as soon as Galactia is done with the painting and hanging for the public, she doesn’t “need him anymore.”

Q: Another character who really stood out was the Doge Urgentino, played by the formidable Robert Ramirez, who cast a different light on a character who I’ve normally seen as being stern and severe. Ramirez captured both sides of his character, the passionate lover of art and the shrewd politician. And he did so with considerable humor. How much coaching did you do to get him to sculpt this intriguing figure?

A: Very little. Robert is an exceptional actor with language, so he was very quickly able to draw out all of Barker’s potency. It’s all in the text – the lines are just sometimes so dense that we skip/gloss over important moments or words. Robert did a wonderful job of bringing a shining sense of clarity to every word, which made his work in rehearsal and performance very sharp. In real life, Robert brings a natural affinity for humor, and I knew the roles was incredibly funny, so casting Robert was perhaps my main accomplishment in terms of what you ask. What Robert did with this role is his, and I just continued to give him a framework to get bigger and more specific with his choices.

Q: Back to your comments in the program book. You ask “how would you [the audience member] respond if you were on the receiving end of the play’s last line, an invitation to dinner. If you were Galactia, what would you say?

A: I hope everyone asks this question of themselves upon seeing this final moment. And in doing so, they might just be tackling some of the more pressing needs of the moment in which we live. Our country has never been more divided, and the world itself seems to be fraying at the seams. After fighting so hard for what we each believe in, are we ‘selling out’ by adjusting our longstanding ideals? In engaging those from the other side of the issue, do we lose the spirit of our ideals? Are we capable of sharing a meal with our adversaries? We are all asking ourselves questions like this in various forms as we negotiate the daily headlines and political landscape of our nation, and our world. Galactia makes her choice, as I suspect we all will have to at some point.

Q: I was so very impressed with the cast of actors selected for the various roles. Even so, Lisa Velten Smith stood out in my mind. So much so, at the end of the play, when the cast came out for its curtain call and much of the audience spring to their feet for an ovation, I purposely waited for Lisa to take a bow before joining in because I wanted to single her performance out in this way. How big a roll did you play in selecting the cast for this production?

A: I cast the show, in deep collaboration with Karla Boos and Quantum Theatre. There were auditions and callbacks about six months ago, and we worked together to find the right actors for the roles and people for the production.

Q: One related question has to do with the set and musical accompaniment. I thought both were so very in tune to the mood of the play. What were you trying to evoke through these two important theatrical elements?

A: Scenes from an Execution is a 19th century play by a British male playwright about a 16th century Venetian female artist, which we are now bringing to life in 21st century Pittsburgh. It’s already a century skipping hodge-podge, and so how do we provide an access point for our audiences?

The first one that is first available to us is: the language. For as dense as it is, and as viscerally gripping as it is, the language is not an obstacle for our audience, like sometimes Shakespeare can be. It is an invitation.

The second access point for the modern audiences is the sharp, crisp, modern design for the transitions. We have 20 scenes, which equals quite a few transitions. We sought for each to have its own journey.

A good set and sound design certainly help cultivate the imaginative world of the play, but they also must serve the needs of the play, so a lot of time was spent understanding what those needs are, and how we can support those needs while simultaneously saying something more about the world.

A play with as many steps and platforms as this one makes everything about power. Every step up or down becomes a metaphor on power, who is winning and who is losing. This set allowed us to be incredibly creative in our staging because every step means something.

Musically, we wanted the music to be a doorway for today’s audiences – making the show fun, unexpected, and energized.

Q: I just found this quote: It’s my duty to see that they get the truth; but that’s not enough, I’ve got to put it before them briefly so that they will read it, clearly so that they will understand it, forcibly so that they will appreciate it, picturesquely so that they will remember it, and, above all, accurately so that they may be wisely guided by its light. -Joseph Pulitzer, newspaper publisher (10 Apr 1847-1911). Do you feel it applies to what Galactia was attempting?

A: I think Galactia may present herself as doing this, but like all human beings, Galactia is deeply complex and full of contradictions. She is ambitious, and yes, she absolutely pushes her agenda into her art. She makes prejudgments and then is surprised and unsettled when she discovers something different. Joseph Pulitzer brought to publishing a moral dignity and journalistic integrity through various forms of transparency. As for Galactia? Well, as she states near the end of the play: “I am not meant to be understood. Don’t you see? Oh, you miserable, well-meaning, always-on-the-right-side, desperate little intellect! Death to be understood. Awful death…”